When visiting Paris this spring, I fell in love with macarons, the tiny almond meringue cookies with buttercream filling that should not be confused with coconut macaroons. Unfortunately, I’m in grad school in a small town in central New York, with only one bakery in town that makes them, so they’re definitely an indulgence. But for my birthday, my boyfriend gave me a book on how to make them!

I’m not that much of a baker. I cook a lot, but bake sparingly—I don’t eat many sweet things, and when I was in high school, I was know to accidentally leave out important ingredients like sugar or flour. While I was excited by the challenge of making macarons, I was also intimidated: the book had about twenty steps just for making the meringue cookie. So I hunkered down and gave it a shot. There’s lots of mixing time required to make it, especially with my tiny handheld mixer, and that left me a lot of time for thinking…how is a meringue made?

I consulted the very helpful On Food and Cooking by Harold McGee. First, in case you’re not familiar with a meringue cookie, they consist of egg whites and some amount of sugar for sweetness. The egg whites are beaten to a froth, sugar is added at some point, and they’re whipped until they become fluffy. Macaron cookies have another ingredient—ground almonds—but they work the same way.

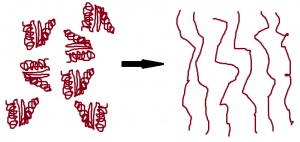

Egg whites are mostly water, with some (about 10%) protein. Proteins are long strings of atoms bonded together that then fold in a certain way. This means that instead of being long and stringy, they are much more compact. These folds are caused by certain weaker interactions than chemical bonds and can be broken apart without destroying the protein molecule.

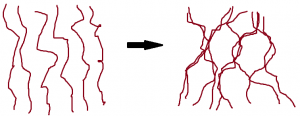

When you beat the egg white, you are doing just that—breaking apart those weak interactions so the proteins end up long and stringy. The physical force of the whipping does this, but the addition of air caused by the whipping helps to displace water so the proteins interact with each other more. As the proteins “unravel” and are surrounded by less water, they tangle with each other. The more the proteins tangle, the more water molecules get moved away, and the tangled proteins start to form the skeleton of the foam around the air pockets.

If you let this foam sit, it will eventually break back down. The proteins that help with the formation of the foam don’t really help to set it more permanently. The addition of sugar can help with this, while also hindering the formation of the foam in the first place. When the sugar is added and dissolves, water molecules surround the sugar molecules, making displacement of the water more difficult, meaning the foam needs to be beaten for longer to form in the first place. Sugar also helps to give more substance to the protein backbone of the meringue foam, however, and its addition will also make the foam shiny or glossy.

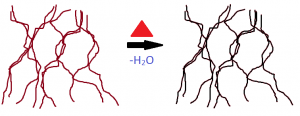

To finally cement the foam structure for the purposes of making a cookie, heating is required. Heating drives off the water (water is what causes the foam to collapse), and causes additional proteins in the egg to unravel and set the foam. Sugar also helps with this step. After heating, the meringue cookie is ready.

Some final notes on meringues: you don’t really want oils/fats or egg yolks (which are mostly composed of fats), because they will take the place of some proteins around the air pockets, but will be unable to provide structural integrity or support. Too much of these will result in a collapse of the foam, or will prevent its development in the first place.

Source: On Food and Cooking by Harold McGee

I never new why it was important not to get yolk in with the egg whites when making a meringue topping for a pie. Thanks for the info!

Love the drawings, really interesting!

Thanks for stopping by, Joe! Glad you liked them!